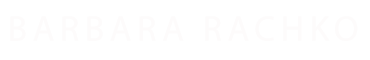

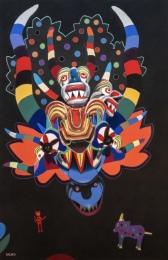

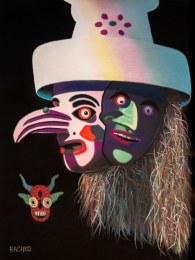

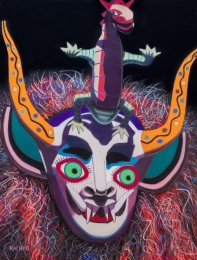

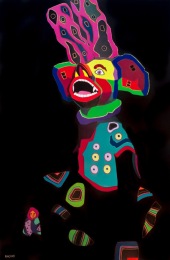

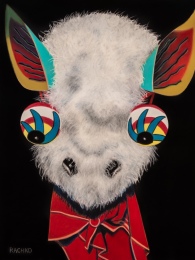

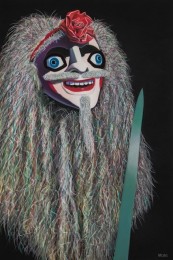

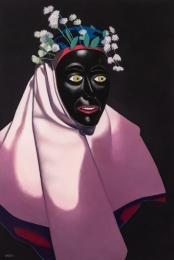

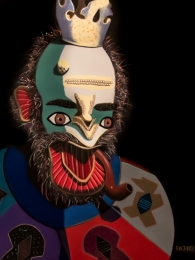

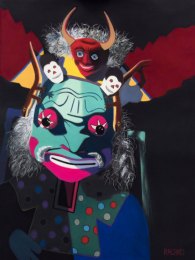

The “Bolivianos” series of pastel-on-sandpaper paintings is the latest evolution of my fascination with traditional masks. In 2017, I was inspired by an exhibition at the National Museum of Ethnography and Folklore in La Paz, Bolivia, featuring fifty Bolivian Carnival festival masks. These masks resonated with my “Black Paintings” series from the previous decade. Each mask was meticulously installed against a dark wall and spotlighted, creating an uncanny effect that sparked new inspiration in my work.

Carnival in Oruro revolves around three great dances: “The Incas,” depicting the conquest and death of Atahualpa; “The Morenada,” representing black slaves who worked in the mines; and “The Diablada,” depicting Saint Michael fighting against Lucifer and the seven deadly sins. These dances use masks derived from medieval Christian symbols with some pre-Columbian elements.

In “Bolivianos,” I evolved the depiction of masks beyond their historic ritual use. Initially, I returned to making photo-realistic pastel portraits. This work is freeing, allowing me to create a rogue’s gallery of beautiful and strong misfits. These pastel paintings have a deeper meaning as universal archetypes of the collective unconscious, resonating far beyond Bolivia to India and elsewhere.

Creating this work is an act of genuine love. I hope the “Bolivianos” series conveys my devotion to soft pastel as a fine art medium and my deep respect and compassion for people around the world.